Reviewed by: Elizabeth Childs, BFA, LMT, SEP

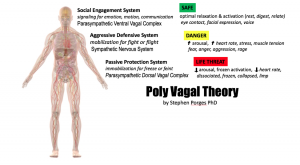

I was intrigued when I first came across Stephen W. Porges’ Polyvagal theory in 2008 reading his article entitled, Don’t Talk to Me Now, I’m Scanning for Danger. Porges’ Polyvagal theory redefined our former understanding of the autonomic nervous system, an understanding which has been in place since the mid 1800’s.

In 2010, at a Somatic Experiencing® training, when my co-trainees and I were grappling with how to apply the theory, we made up lyrics and sang them to the tune of “I Loves You Porgy” from Gershwin’s 1935 opera “Porgy and Bess.”

“We love you Porges, we’re polyvagal,

We love your theory, though it’s complex,

We want to use it, just please explain it,

Write a synopsis, that would be best.

We love you Porges. . . .”

(I’ll spare you the rest, but you get the point.)

Repeated requests at workshops and conferences for a user-friendly synopsis of his scholarly information as presented in The Polyvagal Theory, Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, Self-Regulation (2011) prompted Porges to create his more recent publication, The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory: The Transformative Power of Feeling Safe (2017). Going another step forward, Porges and co-editor Deb Dana published their newest anthology, Clinical Applications of the Polyvagal Theory: The Emergence of Polyvagal-Informed Therapies (2018).

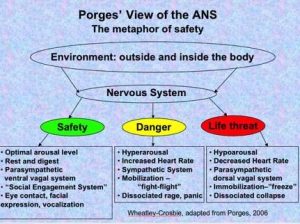

Now, Dana offers her well-developed method of incorporating the Polyvagal theory into clinical practice. In her book, The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy, Dana offers the Polyvagal theory to psychotherapists as an elegant new science-based way of working with the body. At the same time, she offers touch therapists a new paradigm for seeing aspects of the mind. In touch therapy, psychoeducation about the nervous system helps clients understand how body and mind are woven together. Dana’s book offers numerous suggestions towards such psychoeducation. She makes the Polyvagal theory accessible and provides numerous examples of how to implement the theory into clinical work. Beginning therapists especially will find the book helpful with its many suggested maps and methods for using the theory. Fully comprehending the Polyvagal theory can be challenging for non-scientists and section I of the book clearly and succinctly explains how the autonomic nervous system evolved into three parts; the dorsal vagal, the sympathetic and the ventral vagal system. Advanced therapists not familiar with the Polyvagal theory or with the nervous system in general will appreciate this section.

Dana explains the Polyvagal theory’s discovery of the most recently evolved part of our autonomic nervous system, the ventral vagal nerve, also called the smart or mammalian vagal. This “wanderer” nerve, which shares the same root as the word “vagabond”, is specifically evolved to permit social interaction in an environment of perceived safety without using the large amounts of energy required by the fight, flight or freeze actions of the nervous system. Porges’ paper over ten years ago entitled, “Love: An Emergent Property of the Mammalian Autonomic Nervous System” (1998) discussed this and reading that was when this curious bodyworker became inspired to study the psyche.

As a bodyworker with extensive experience, and as a counselor-in-training, I absorbed Dana’s book from both perspectives. As a bodyworker, I use the Polyvagal theory in my work with patients who have suffered from the medical trauma of invasive cancer treatments by doing hands-on work to bring more tone to the ventral vagal system. I help create a safe environment through the use of prosody, expressiveness and reassuring touch. Often when providing bodywork, I teach Stough Breathing Coordination to patients. Breathing Coordination, developed by Carl Stough in the 1960’s in New York City, was originally developed for professional vocalists and speakers, wind instrumentalists and elite athletes. Later Stough successfully used it to help patients suffering from emphysema and COPD. Breathing Coordination elevates vagal tone by building the ideal physiological coordination of all muscles of respiration while at the same time using and stimulating laryngeal and auditory muscles.

As a beginning psychotherapist, I appreciate the varied suggestions Dana offers such as using movement, sound, breath, play, mapping, and other various ways of educating and guiding clients. She touches lightly on these topics. Although my patient population wouldn’t be amenable to mapping and charting because of their acute medical conditions, I think Dana’s offerings of those charts and maps, her “beginner’s guide” and her explanation of the neuroception of safety and non-safety will be a helpful guide for new therapists. By using regulating maps and tracking exercises, the suggestions in section II and III offer ways to understand and track the physiological platforms that underpin psychological states. Advanced practitioners may want to develop their own ways of implementing the Polyvagal theory in ways that will be more attuned to their work. For example, Somatic Experiencing® practitioners may incorporate the Polyvagal theory in their use of interoception, tracking sensation, pendulation, titration, movement and gentle hands-on work. Dana offers a science-based understanding of the physiological shifts a client may experience during face-to-face interaction in a therapeutic relationship. Reading her book supports and confirms my understanding of the value of skillful person-centered talk therapy. Understanding how neurophysiological states affect feelings and behavior provides another lens through which to view what happens during the kind of relationship-based therapy that includes congruence, genuineness and empathic understanding. From a Polyvagal perspective, the client experiences a shifting towards ventral vagal engagement as he/she moves away from the sympathetic charge of defensiveness. Trust created through the therapeutic relationship creates feelings of safety, and with this new understanding, the client can understand this both on a cognitive and a sensory level.

Mainstream culture understands the nervous system as it concerns fight/flight vs. the relaxation response. We know now that this understanding is inadequate. While the mainstream culture does know that fight/flight reactions to trauma or extreme stress are an unconscious response, we now understand that there is also a freeze reaction that can happen beneath consciousness as a response to perceived or real danger when fight or flight can’t happen. And fight or flight often cannot happen. This understanding of freeze as an unconscious response is an enormous help in describing natural reactions to thwarted fight/ flight in the face of dire threat. Dana explains to therapists the importance of understanding that freeze is an evolutionary unconscious response to danger or perceived threat, and how freeze, or “collapse” as Dana often refers to it, comes into play when other defense responses don’t work. She shows how disassociation and depression are related to this autonomic unconscious response and suggests ways of educating clients in working with this. I am curious about what is happening in the body as it moves between dorsal vagal, sympathetic and ventral vagal states and I was especially interested in Dana’s discussion about how clients shift through these nervous system states. I look forward to future exploration and a more in-depth understanding of the qualities, variations and subtleties of those state shifts.

Mainstream culture understands the nervous system as it concerns fight/flight vs. the relaxation response. We know now that this understanding is inadequate. While the mainstream culture does know that fight/flight reactions to trauma or extreme stress are an unconscious response, we now understand that there is also a freeze reaction that can happen beneath consciousness as a response to perceived or real danger when fight or flight can’t happen. And fight or flight often cannot happen. This understanding of freeze as an unconscious response is an enormous help in describing natural reactions to thwarted fight/ flight in the face of dire threat. Dana explains to therapists the importance of understanding that freeze is an evolutionary unconscious response to danger or perceived threat, and how freeze, or “collapse” as Dana often refers to it, comes into play when other defense responses don’t work. She shows how disassociation and depression are related to this autonomic unconscious response and suggests ways of educating clients in working with this. I am curious about what is happening in the body as it moves between dorsal vagal, sympathetic and ventral vagal states and I was especially interested in Dana’s discussion about how clients shift through these nervous system states. I look forward to future exploration and a more in-depth understanding of the qualities, variations and subtleties of those state shifts.

Readers will appreciate the way the theory is put forward in an accessible way. However, Dana’s approach to explaining the Polyvagal theory by using a ladder as the primary metaphor for visualizing the complexities of the nervous system (p. 10) is frustrating to me in its simplicity and seems inadequate to describe this system which has evolved over hundreds of millions of years. It makes me wonder if this book really should be recommended for beginning therapists only. The ladder explanation raises questions for me:

• Do people move through these cycles so swiftly in day to day living as the author implies?

• Do her clients move in and out of states so thoroughly, as she states?

• Or do some people tend to be in a fight/flight sympathetic state most of the time, while perhaps others are more prone to dorsal vagal state at times.

I found the descriptions somewhat confusing as I read her accounts. Dana seems to imply that we move in and out of dorsal vagal states easily. That seems counter-intuitive to me. Dorsal vagal appears to be an extreme state, not one that is entered and left so easily. I see people in the hospital who have endured extreme or drastic surgeries and find that a dorsal vagal state could describe their experience, but to go in and out of this state easily and swiftly in daily life, I find unconvincing, so would appreciate more clarity about defining these states. And if, as Porges (2011) shows— heart rate variability helps define vagal tone— are there are biomarkers for the dorsal vagal state that can be measured? If a person is prone to becoming stuck in one state and has difficulty regulating, that is one thing, or if there is a tendency to move towards one state because of one’s history, another, but to move in and out so frequently? Also, ventral vagal regulation, I would assume, is a constantly accessible and variable state, with levels of regulation, and not a state to be completely in or out of. Porges refers to vagal tone, and more clarity about using this term in Dana’s book would have been helpful.

There is also mention of disease as it relates to nervous system states. I see the value in understanding and questioning how the body is affected by nervous system states, but since so many variables contribute to disease, I am often skeptical when I hear of disease being attributed to primarily one thing, even if that one thing is as broad as dysregulated nervous system states (p. 11-12.)

I also wonder about clients who could be described as “highly sensitive people”, as in Elaine Aron’s understanding as stated in The Highly Sensitive Person (Aron,1996). How is this 15-20{f4ab6da3d8e6a1663eb812c4a6ddbdbf8dd0d0aad2c33f2e7a181fd91007046e} of the population affected by these different autonomic nervous system states? Do they more easily move in and out of states? Is one state more likely? What about the spectrum we use to describe the inclination of our clients and ourselves to be introverted/ extroverted?

It seems as if the lens of ventral vagal regulation that Dana describes leans heavily towards constant social interaction as if that is always the best regulator when it is clear that constant social interaction is highly dysregulating for many people. Clearly ventral vagal state is achieved in other ways too, not just by social interaction. Dana does address this in self-help suggestions, but more could be offered on this important aspect of helping create resilience and healing unresolved trauma. And lastly, surely the Polyvagal theory is not only appropriate for trauma survivors, so more mention of the experience of daily life would be welcome. If we look at the experience of daily life through this new Polyvagal lens, how does it change our understanding of, and our actual experience of being alive?

It seems as if the lens of ventral vagal regulation that Dana describes leans heavily towards constant social interaction as if that is always the best regulator when it is clear that constant social interaction is highly dysregulating for many people. Clearly ventral vagal state is achieved in other ways too, not just by social interaction. Dana does address this in self-help suggestions, but more could be offered on this important aspect of helping create resilience and healing unresolved trauma. And lastly, surely the Polyvagal theory is not only appropriate for trauma survivors, so more mention of the experience of daily life would be welcome. If we look at the experience of daily life through this new Polyvagal lens, how does it change our understanding of, and our actual experience of being alive?

The Polyvagal theory is deeply interesting to anyone interested in human behavior, neuroscience and evolution. It is invaluable for those of us who are working with patients impacted by trauma, in showing how large and small trauma impact the ability of our bodies and minds to regulate and maintain a wide window of resilience. Deb Dana’s book offers clinical applications and explains various aspects of emotion and behavior through the lens of the Polyvagal theory. Her explanation is easy to grasp, and her translation of the theory may be extremely helpful in working with and explaining the theory to colleagues and patients.

Deb Dana, LCSW, is a clinician and consultant specializing in helping people safely explore and resolve the consequences of trauma. She is the creator of Rhythm of Regulation training series and teaches internationally on the ways Polyvagal Theory informs clinical interactions with trauma survivors.

Elizabeth Childs, BFA, LMT, SEP has practiced bodywork for over 40 years, and is currently a senior Massage Therapist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. She is also a professional jazz singer. Currently she studies at Hunter College towards a Masters in Mental Health Counseling.

References:

Dykema, R. (2006). “Don’t talk to me now, I’m scanning for danger”, How your nervous system sabotages your ability to relate: An interview with Stephen Porges about his polyvagal theory. Nexus (March/April), 30-35.

Porges, S. (1998). Love: an emergent property of the mammalian autonomic nervous system. Psychoneuroendocrinology, Vol.23, No.8, 837-861

Image Credits with gratitude for their use:

Breathing: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mtRrxNTnyh8

Polyvagal Theory: http://www.presence.academy/porges-poly-vagal/

Porges View of ANS: https://attachmentdisorderhealing.com/porges-polyvagal3/

Interested in buying the book? Please use the link below. The few pennies we receive allow us to continue offering quality reviews, articles, interviews and more for free to our readers.