By William Ferraiolo

Reviewed by Nancy Eichhorn

I recently reviewed A Life Worth Living: Meditations on God, Death, Stoicism by William Ferraiolo. While reading, I was drawn to understand Stoicism more deeply, to read more about Marcus Aurelias and Epictetus, two Stoic writers that Ferraiolo quoted throughout the text. Ferraiolo’s discourse was educational with a knowledgeable authorial tone.

So, when I started to read the advance PDF of his soon-to-be-released You Die at the End: Meditations on Mortality and the Human Condition (June 2020), I felt frustrated by his confrontational style, a voice I had experienced before when I reviewed Meditations on Self-Discipline and Failure (Ferraiolo, 2017). To cite numerous clichés, he doesn’t sugar coat or mince words. He is direct, to the point, calls a spade a spade and makes no bones about it. At times his “brutal confrontational” style may be off putting (more on this later) but yet, I read the book, so that tells you something.

You Die at the End consists of 180 “meditations”, Ferraiolo’s “ruminations” in response to Biblical scriptures, Old Testament writings. Early Stoics believed in a higher power (Zeus, God, the Universe) so Ferraiolo’s use of Christian scriptures was not surprising.

According to his introduction, the Biblical excerpts touch on topics that are “directly or obliquely related to the subject around which the meditation centers. This should not be interpreted as an endorsement, or as a rejection, of the Bible passage quoted in each case or of the lesson contained therein. This approach is merely a matter of this author ruminating about elements of the human condition that were sufficiently interesting to make their way into scripture. The fundamentals of a human life on this planet have not changed so very much over the millennia. The world is large and indifferent to the suffering of its denizens, its inhabitants. Perhaps there is a God who is not indifferent. Perhaps there is no such God. There are, however, people who suffer” (pg.5).

Each scripture is followed by Ferraiolo’s interpretation of and implication in our lives today. His ‘ruminations’ typically start with a question—a guide to look within, to assess our self-perceptions and reasons for being— followed by startling reflections and revelations. Adhering to Stoic precepts, Ferraiolo does not appear to care what others think (one’s reputation is an external event that we cannot control) nor does he allow room for self-pity or self-aggrandizement. He talks directly to the reader, the text is written in second person: YOU. His words loud and clear. He does not hold back.

“If you do not concern yourself with your cat’s opinion of your character, and you really should not do so, what excuse do you offer for allowing yourself any preoccupation with what your colleagues, relatives, or neighbors think of you? Your colleagues, relatives, and neighbors are, presumably, wiser and more perceptive than your cat. . . Nonetheless, suppose that the humans, the talking primates of your acquaintance, are, in fact, intellectually superior to your stupid cat—the one that you step on several times each day. Does this give the humans’ opinion of you some special purchase upon your imagination? The contents of their minds are entrusted by God, or by nature, to them—and you ought not concern yourself with anything not entrusted to you. What rattles around in their heads need not be any problem for you. Such concerns are, to say the least, unbecoming. Be more like your cat insofar as disregard for humanity is concerned. Better to bat about a ball of yarn than to investigate the ruminations of imbeciles. In the former case, you might get to keep some yarn.”

Within a paragraph or two, you are directed to consider: Do you let other people’s opinions of you matter? Do you give away your sense of self by worrying with situations you cannot control? Are ‘ruminations of imbeciles’ a worthy endeavor?

The book follows this pattern throughout. Readers are invited to sit and consider. Contemplating Ferraiolo’s writing style—both the second person and the use of language that I find demeaning and insulting at times, I became curious about Marcus Aureoles’ writings. What was his tone? Words like stupid, imbecile, idiot and such pepper Ferraiolo’s text. I wondered, is this how Stoics write?

Research

Marcus Aureoles’ writings in Meditations were meant to remind himself to remain at peace in this world. They were part of his discipline to deny himself the luxury of self-pity; he had many losses in his life yet remained steadfast in his belief that “everything that happens is a natural occurrence, in the hands of a benign intelligence that ran through all things”. He writes simply of what he learned from teachers, from life. He talks of character and humility, of freedom of will, of self-government and cheerfulness in all circumstances. His writings are fascinating.

According to Aureoles, there was no such thing as tragedy; our interpretation of said events create our suffering:

“The Universe is good and only has the best intentions for humanity. It’s up to you, your choice to interpret those intentions, correctly and find peace of cling to one’s impression and suffer.”

On death, he wrote:

“It is good to you, O Universe, it is good to me. Your harmony is mine whatever time you choose is the right time. Not late, not early. What the turn of your seasons brings me falls like ripe fruit. All things are born from you, exist in you, return to you” (IV.23).

While he believed that Logos controls all things including one’s fate, he also stressed that we have the freedom to choose how we relate to the circumstances in our lives.

And while reading Aureoles’ Meditations, also written in second person, I saw hints of his approach in Ferraiolo’s book. For instance, Ferraiolo’s meditation on page 226:

“Do not fret about life after death, the world to come, resurrection, reincarnation, heaven, hell, purgatory, or any of the other post-mortem possibilities suggested by scripture, wisdom traditions, or superstition. Live this life as well, as reasonably, and as virtuously as you can manage. Do your best to be upstanding and honorable. If there is something after this “vale of tears,” then a life of decency should be sufficient to secure a palatable version of the possibilities allegedly on “the other side.” Sustained decency might just get you to heaven. If, on the other hand, there is no life, no experience, no continuing consciousness beyond this terrestrial sphere, then you have exactly as much reason to try your best to become as wise, as virtuous, as decent, and as upstanding as you would have if the road to heaven lay open before you. Do not be good for the sake of gaining paradise. Do not pursue wisdom and virtue for the sake of applause, accolades, or the approval of other persons. That is shallow, cynical, and self-serving “virtue.”

But then I felt his tone shift:

“Indeed, there is nothing especially virtuous about pursuing narrow, material self-interest. If there is a God, He will see through the ruse, and your ersatz efforts will be for naught. Why would the Lord reward selfish egoism? As for the opinions of other persons, since when was the pursuit of public approbation listed among the admirable endeavors? If there is not a God, you owe it to yourself, and to those who depend upon you, to live the most fulfilling and flourishing life you can. You will find it difficult to be a decent parent, spouse, or citizen if you do not even manage to live the life of a decent, honorable human being. What is flourishing without wisdom and virtue? Leave the pursuit of pleasure to pigs, children, and celebrities.”

I started to write that Aureolo’s tone was not demeaning when I paused. I heard myself complaining and thought, wait a minute. I chose to read Ferraiolo’s book. My choice. No one made me read this. And in the space of that pause I realized that I am drawn into Ferraiolo’s text despite adverse feelings. I read and reflect. I spend time researching to expand and explore, and in fact I stretch and grow.

I think this is part of Ferraiolo’s skill as a writer and a teacher (he teaches philosophy at San Joaquin Delta College). Teachers challenge us. We aren’t supposed to accept everything they say as the Gospel truth. They are humans, too. They offer their interpretation, their opinion. Their story is laced with their experiences, their beliefs, their faith. No one has the answer, just questions. And, when posed well, they invite us to delve within.

I recalled my Grandfather, a German Lutheran minister in a small midwestern congregation (his story filled with wars and revolutions, famines and economic down turns resulting in The Great Depression, and intense loss across continents). He wrote letters filled with scripture, shared his take on how these words impacted his life and in turn provided lessons to help me change mine. I was supposed to accept his teachings as truth. I grew up with the Bible being the word. As a young woman, I challenged that word, felt it was biased, an interpretation from a male dominated perspective. And yet, it was one interpretation of life and how I might benefit from other people’s experiences.

Ferraiolo appears to be offering a chance to consider Biblical scriptures (not the Bible in its entirety but specific passages) and how he views them today in terms of what we, as readers, might consider from a Stoic perspective. However, he does not tell us how to think or feel; rather, he offers meditations/spiritual lessons to encourage self-reflection. What we do with it is up to us.

Coming Attractions:

Not surprising, Dr Ferraiolo has two more books on the way—this man is prolific:

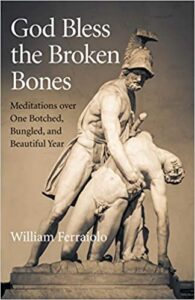

God Bless the Broken Bones: Meditations over one Blotched, Bungled and Beautiful Year (September 25, 2020)

God Bless the Broken Bones: Meditations over one Blotched, Bungled and Beautiful Year (September 25, 2020)

According to advance reviews:

“God Bless the Broken Bones won’t tickle your ears with pleasant words. Instead what you’ll find is a year of one man’s seemingly uncensored thoughts, fears, frustrations, longings, gratitude, and self-exhortations. Raw yet eloquent, William Ferraiolo’s musings reveal the daily challenges to living a life of equanimity and honor, and why there’s no worthier goal. At times this book might offend you. It will certainly challenge you. And if you’re willing, it might change you. I recommend you see for yourself.” Seth J. Gillihan, PhD, author of Retrain Your Brain: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in 7 Weeks.

Slave and Sage: Remarks on the Stoic Handbook of Epictetus (February 2021).

William Ferraiolo received a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Oklahoma in 1997. Since that time, he has been teaching philosophy at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, California. His books include: Cynical Maxims and Marginalia, Meditations on Self-Discipline and Failure: Stoic Exercise for Mental Fitness, A Life Worth Living: Meditations on God, Death and Stoicism, You Die at the End: Meditations on Mortality and the Human Condition, and God Bless the Broken Bones: Meditations Over One Botched, Bungled and Beautiful Year.

Photo Credits:

Bible with note pad: Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

Cat Manja Vitolic on Unsplash

Meditations cover Wikipedia

Bible covers: Chuttersnap on Unsplash