By Jan Winhall

Reaching beyond the western, post Descartes view of mind/body duality as distorted and harmful, I have explored alternative ways of experiencing and conceptualizing the body. I think this is critical when working with addiction because our current understanding and treatment of addiction reflect this disembodied view—addiction is seen as a malfunctioning of our computer-like brains. But the current brain disease model is failing us. Rates are soaring. People are dying in the streets. We can and must do better than this.

To approach addiction from a new perspective, I created a model to conceptualize and treat addiction: The Felt Sense Polyvagal Model (FSPM). FSPM addresses addiction where it lives, in the body. Based on over 40 years of client interactions, the model understands addiction as an adaptive attempt to regulate emotional states. Addictive behaviors are self-soothing strategies to survive when we cannot calm ourselves, and they are self-harmful. These behaviors do not come from sickness however, they come from a bodily response to threat and a wired-in survival mechanism.

From an embodied place of experiencing, and through the lens of Polyvagal Theory, we can understand addictive behaviors as the body’s attempt to keep us alive when being in the present moment is too overwhelming. Shifting to a bottom up approach allows us to experience both the wisdom of the body, and the wisdom of addictive responses.

To create the FSPM, I drew from Stephen W. Porges’ Polyvagal theory (2011), which offered a new understanding of the autonomic nervous system. As I began to learn about Polyvagal Theory, I realized that it enhanced my understanding of what I knew intuitively: Clients were using addictive behaviors to propel themselves from a state of sympathetic arousal to a dorsal vagal response of numbing, and vice versa. Through the lens of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), we see these behaviors as adaptive. While they may look bizarre, they have a logic of their own that is oriented towards survival. This understanding is key to appreciating the vital importance of Porges’ discovery.

Why is this so? Because it validates these behaviors as adaptive, and the folks who rely on them as, in a sense, normal. Polyvagal Theory teaches us that we respond to threat in a very elegant and systematic way, first by activating the ventral branch of the vagus nerve, our ‘smart’ vagus. If the situation cannot be resolved in this way, the sympathetic branch kicks in to empower us to mobilize. If mobilizing is not possible, we have a third option available to maximize our potential for survival, the dorsal branch of the vagus nerve that shuts us down, helping us to dissociate, to bear the unbearable.

This is vitally important because we then see traumatic responses in a new light. A paradigm shift is demanded of this new light. A shift that honours the body’s inherent knowing, healing shame and blame, and putting new and more body- informed healing practices into the forefront.

Many other cultures and movements never lost their appreciation for the wisdom of the body. Our culture lost its way post Descarte. We have much to learn and unlearn. My own understanding came from the Feminist movement. We embraced body wisdom, and intuitively understood traumatic responses, including addiction, as inherently helpful. But our female voices were not respected, and we didn’t have a significant piece that Polyvagal theory provides. That is, a sophisticated understanding of the autonomic nervous system that provides a neurophysiological explanation for traumatic/addictive responses, and the power of a scientific language that speaks to, and challenges, our post Descarte era. Porges’ capacity to integrate top down and bottom up ways of knowing is making him a powerful contributor, a change agent in our currently desperate culture of global trauma.

My work is also influenced by Eugene Gendlin (1978), who coined the term felt sense based on a contemplative practice called Focusing. Focusing is a six-step process that helps us find our implicit embodied knowing about an issue in our life. A knowing that is at first vague. Turning attention inwards and listening with compassion allows a felt sense, a whole sense of the situation, to form.

Thoughts, feelings, physical sensations, and memories are different aspects of experience that create a pathway into the Felt Sense. In asking questions about these aspects we help the client to deepen their embodied knowing of the issue. As the felt sense forms we pause and stay with the fullness of experiencing. Sometimes a Felt Shift, a physical release happens as the client integrates a new knowing. This shift is the bodies’ knowing and pointing in the direction of growth and healing. The client feels a relief, a settling. Focusing is a natural process that happens all the time. Gendlin found that clients who were doing well in therapy were connected to their bodies. They had access to a Felt Sense. However, because we live in such a disembodied culture, many clients needed help to connect, so Gendlin created the steps.

I also incorporated Marc Lewis’ s learning model of addiction. Lewis, a neuroscientist, reinterpreted the neuroscientific data on addiction from what he called a disease-free bias. He reframed addiction as the development of coping habits within a social matrix. “According to Lewis, addiction is an extreme outcome of a normally functioning brain” (Snoek and Matthews, 2017).

In addition, I’ve brought an anti-oppressive lens to the understanding of the root causes of addiction. It is from this lens that we have seen the profound impact that oppression has on the development and increasing incidence of addictive behaviors. Experiences of oppression lead to trauma, and trauma is the underbelly of addiction. Consequently, marginalized groups are much more vulnerable. Staci Haines, author of The Politics of Trauma, (2019) puts it so well when she says that trauma robs us of safety, belonging and dignity. Without these basic needs being met, we seek out quick and dirty ways of soothing to help us survive.

My objective was to provide a teaching/clinical model of addiction that offered a radical paradigm shift, challenging our current pathologizing approach. I integrated new neurobiological findings in brain research, supported by an alternative learning model of addiction, as well as subsequent clinical approaches that address embodied trauma therapies.

My goal was for therapists to understand addiction using a sophisticated theoretical framework and treatment strategies that challenged old, disembodied approaches. The model is adaptable to any school of psychotherapy or healing practice.

The Felt Sense/Polyvagal Model

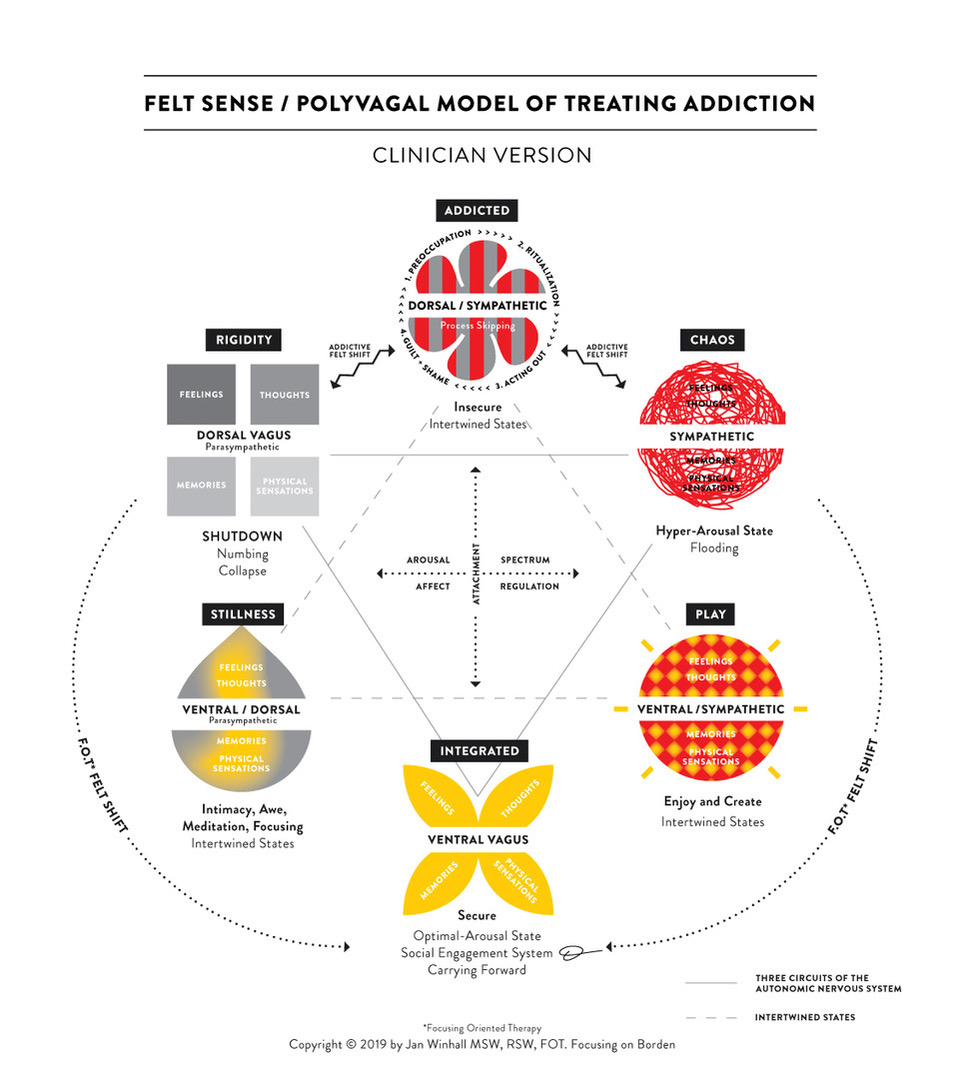

To support FSPM, I created two graphic models. One for clinicians and one for client use. Looking at the graphic depiction of the FSPM Clinician version we can see the overlap with Porges’ work.

First are the three circuits of the ANS, connected via a solid lined, inverted triangular

A) the ventral vagus is in yellow at the bottom of the page,

B) the sympathetic in red on the right, and

C) the dorsal vagus is in grey on the left.

Next are the Intertwining States, connected by the dotted line triangle.

Intertwining states are states in the system that utilize two pathways. The ANS has the capacity to blend states creating a greater range of experiences. The intertwining states are represented in the model in mixed colors.

A) Play is on the bottom right in yellow/red.

B) Stillness is bottom left yellow/grey.

C) And the FSPM proposes a third intertwining state of Addiction, which is at the top of the model, red/grey.

As a state, Addiction is a blending of sympathetic and dorsal. Without the presence of the ventral vagus, the Social Engagement System is offline. When trauma and other states of emotional dis-regulation occur, the capacity to regulate through the ventral vagus are compromised. The ANS shifts into survival mode. People then employ addictive behaviors to seek relief from suffering.

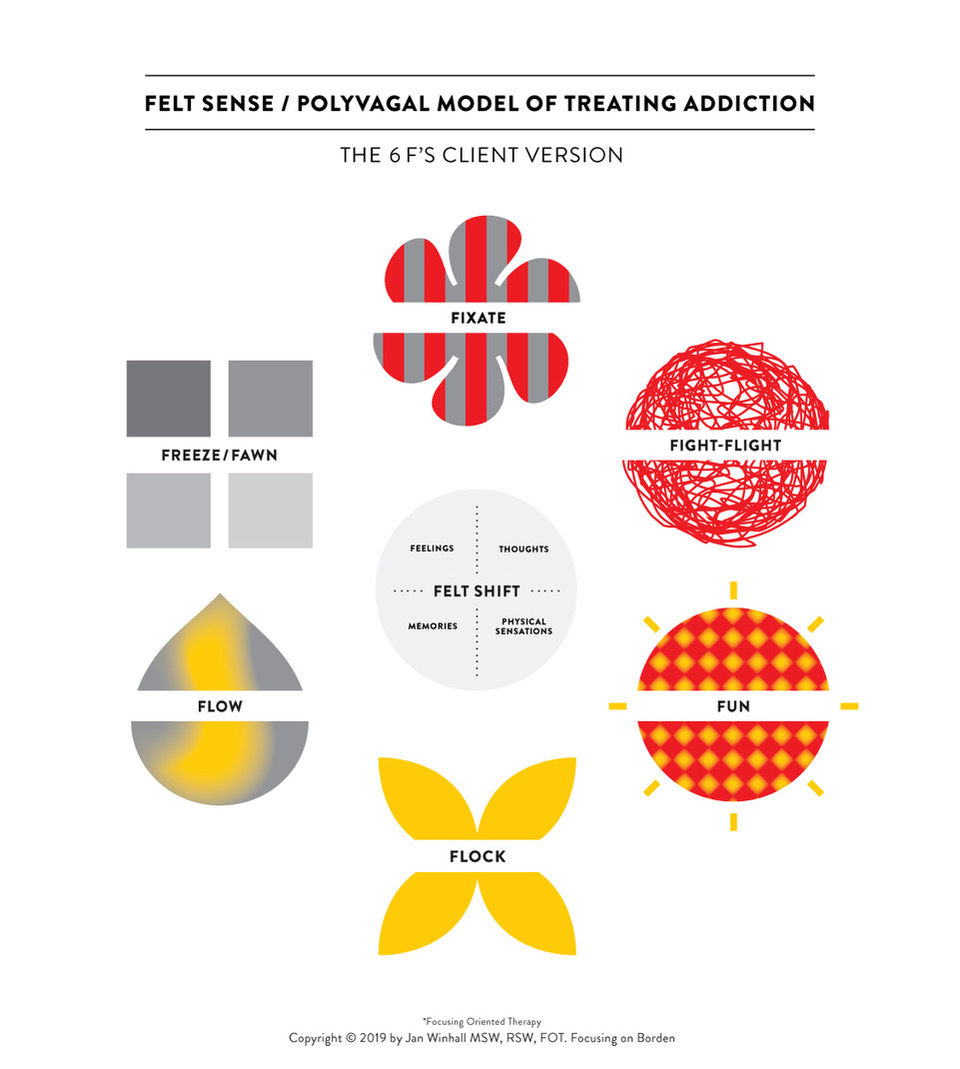

In addition to providing a new map for clinical applications, I created a simple version for clients that uses what I call the ‘Six F’s’ to define the states of the autonomic nervous system: Flight/Fight, Fawn/Freeze, Fixate, Flow, Fun, Flock.

1. Sympathetic Response: Flight is a state of fear and anxiety. In this state the body mobilizes to run and escape. Fight is a mobilizing state of anger.

2. Dorsal Response: Fawn is a state of surrendering to someone with power over you. Freeze is a collapse of the ANS into a dissociative state when sympathetic response is ineffective.

3. Fixate is the intertwining state of addiction that acts as a propeller between Flight/Fight and Fawn/Freeze.

4. Flow is an intertwining state between ventral and dorsal. A state of safety with stillness.

5. Fun is an intertwining state between ventral and sympathetic, a state of playfulness.

6. Flock is the ventral state of grounding and safety.

With time our clients learn how to identify and track the state they are in and to use the tools that we teach them to move more into the ventral vagal state.

Applying the Model

I offer an example starting with Focusing. A client comes in with anxious feelings and a tightening in her throat. She says that she doesn’t know why she feels this way. We begin the process of quietly turning attention inwards, down into the centre of the body. Tears come as she connects the physical sensations with the feelings of sadness and anger. A beginning of the Felt Sense starts to form. I ask, “Can you welcome both feelings?” She pauses and explores where there are no words. She puts a hand on her throat.

“I don’t know how to be with anger,” she says. More sensing into the body.

More tears flow as she feels the physical sensations of the Felt Sense flooding into her throat and now down into her chest. A whole Felt Sense of her situation forms: thoughts, feelings, physical sensations, and memories.

“This goes way back for me. Little girl afraid to be angry, so I cry instead. “And”, she stops, hesitating to say the next sentence, “I eat. A lot. And then I make myself sick to get rid of it. This needs to stop. I need my anger.”

Her whole body moves and relaxes with a Felt Shift. She feels her throat loosening, a new piece has come for her. An explicit knowing that has great meaning for her. A need to connect with her anger. Her Felt Sense carries this meaning forward into her life as she welcomes what came in her Focusing practice session.

Next, we can map the felt sense onto the Felt Sense Polyvagal Model to integrate the autonomic nervous system states. This gives us more information about the client’s journey. In the Clinician version she moves back and forth from chaos/sympathetic meme, over to rigid/dorsal (fawn), a shutting down of anger and surrender of power, then down to Integrated/Ventral meme in her Focusing Oriented Psychotherapy session. Together we look at the Client Version of the model as she maps her journey from Flight/Fight to Fawn to Flock.

In Conclusion: A Call to Action

Polyvagal theory teaches us that we are not safe until all of us are safe, feel a sense of belonging, and have dignity in our lives. Because we coregulate each other, we are designed to live in community. We thrive when we are taking good care of the most vulnerable folks in our culture. Addiction is created and prolonged by states of vulnerability.

At a time like this, with a global pandemic upon us, we need more than ever to learn the lessons of a Polyvagal informed society. We need to learn from folks suffering from addiction. They tell us where we are failing as a culture, and what we must do to bring safety to each and every one of us. If we all need to go home and practice social distancing, then we better make sure that all of us have a safe home to go to. Otherwise, none of us are going to be safe.

“Addiction is our teacher,” says Bruce Alexander (2010), a researcher and author. In his documentary, Addiction: The View from Rat Park, he shows us how we have lost connection with each other and with the natural world. In our disconnected state, we, as a culture, can’t know how to feel into the problem or the solution. We cling to our top down explanations of demon drugs to avoid feeling into the embodied cultural trauma of our times. Like the addicted soul, we delude ourselves. We have lost our way. But only in our heads. The body knows the answer.

Addiction is a political problem, and I invite you to join me in standing up and speaking up to make a difference!

I am currently writing a book about the FSPM model. For information and questions please visit my website: http://www.focusingonborden.com/

Jan Winhall, M.S.W. R.S.W. F.O.T.T. Toronto, Canada. Jan is a psychotherapist in private practice and Director of Focusing on Borden, a centre for teaching Focusing and Focusing-Oriented Therapy. Jan is the author of Understanding and Treating Addiction with the Felt Sense Experience Model. In Emerging Practice in FOT. Jan teaches internationally and is a lecturer in the Faculty of Social Work at the University of Toronto. She is currently writing a book about her new Felt Sense/Polyvagal Model for treating addiction.

References

Alexander, B. K. (2010). The globalization of addiction: A study in poverty of spirit. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Gendlin, E. (1978). Focusing. New York, NY: Everest House Publishing.

Haines, S. (2019). The Politics of Trauma. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books.

Lewis, M. (2015). The Biology of Desire. Canada: Penguin Random House Doubleday Canada.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, self regulation. New York, NY: W. W. Norton and Company.

Snoek, A., & Matthews, S. (2017). Introduction: Testing and refining Marc Lewis’s critique of the brain disease model of addiction. Neuroethics 10(1): 1-6. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5486510/

PHOTO Credits

Woman crying: Kat J on Unsplash

Group hug: Dimitri Houtteman on Unsplash

All other photos from SPT magazine archives