Spring Issue Articles

Submitted by:

Sally Dear-Healey, Ph.D., PPNE, CBE, Doula

“Therapists will have much more impact when they are able to conceptualize or discern more precisely what this client’s core problem really is, how it came about developmentally, and how it is being played out and causing symptoms and problems in his (or her) current life”

(Teyber, 2010, p. 7).

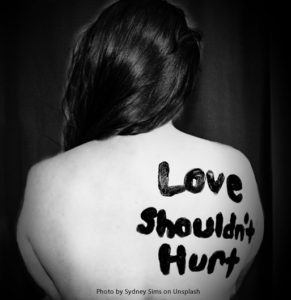

The memoir you are about to read is a disclosure of personal and familial experiences with family violence. More specifically, it highlights experiences of child neglect and abuse, sexual assault, and intimate partner violence, as well as the emotional and physical symptoms that often result. Because it contains graphic and potentially overwhelming information it may not be easy to read. In fact, some of my experiences may trigger somatic reactions, resulting in sensed feelings of discomfort, shock, and perhaps shame. The point is, this was and is my reality, and I invite and encourage you to read it in its entirety. The story does have a happy ending and it clearly illustrates important concepts in trauma-informed awareness.

I offer my story as an impassioned call for therapists, clinicians, and teachers to better understand prenatal and perinatal psychology and trauma informed practices. According to SAMHSA’s concept of trauma-informed approach we need to 1) Realize the widespread impact of trauma and understand potential pathways for recovery; 2) Recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved it the system; 3) Respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and 4) Seek to actively resist re-traumatization (https://www.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions). This is critical not only for self-care, but also for client care, a lesson some of us don’t learn until later in our lives and careers. In fact, it wasn’t until I began studying prenatal and perinatal psychology and enrolled in the Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology Educator (PPNE) Certificate program offered by The Association for Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health (APPPAH), that I realized the extent to which my history impacted my subsequent, yet not entirely conscious beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors, as well as my relationships and the career paths I took. I also became acutely aware of how my own unhealed imprints impacted my relationships with my clients and students. This is because unhealed wounded healers, by virtue of the Law of Attraction, tend to attract clients who have wounds and issues similar to theirs (Weinhold, 2018).

In retrospect, it comes as no surprise that for twenty years I worked as a childbirth educator, doula, and apprentice midwife. And then, for the next twenty years taught courses such as Family Violence, Sociology of the Family, and Couples and Family Therapy. I also became a domestic violence (DV), intimate partner violence (IPV), rape crisis counselor; family mediator; and more recently a divorce mediator. Birthing and mothering my own children and doing my life’s work has been my way of making the world a better and safer place. It has also been a path of self- discovery, repair, and healing. Everyone has their own unique story that needs to be heard. This is mine.

In the beginning

Chamberlain (2014) states “To be born unwanted may be a baby’s greatest peril” (pg. 7). I began my life unwanted. My birth mother already had two daughters, no husband, and was working multiple jobs just to survive. She had not intended to get pregnant nor did she ever plan to keep me. When I found my birth family in my fifties, I discovered two (half) sisters, products of an abusive relationship and a (full) sister that had been given away three years before me, also at birth. While I knew I had been adopted when I was six months, I didn’t know that I had spent the previous months in an orphanage. Hearing that news made me extremely sad, but it also explained the feelings of abandonment and insecurity I had felt most of my life. It also makes sense from an attachment perspective since it is highly unlikely that I had the benefit of a caring adult, or what Michael Trout (n.d.) refers to an “Aunt Rosie,” in those critical early days and months.

Although my adoptive parents told me they got to “choose me,” I never felt unconditional love, especially from my mother. My parents, who were born in the early 1900s and were in their early forties when I was adopted, utilized corporal punishment to deter and punish unwanted behaviors. I was frequently spanked, slapped, hit with a belt, and sent to my room so I could “think about what was wrong with me.”

One of the main things I learned in my PPNE work, and later trauma informed studies, is that instead of asking ‘what’s wrong with you,’ we should be asking ‘what happened to you?’ or ‘what didn’t happen to you.’ From a clinician’s perspective this means that we need to have a comprehensive understanding of the widespread prevalence and effects of trauma, as well as the ways in which trauma can – often unconsciously does – influence emotions, behaviors, and the development of coping strategies.

My mother, who I believe carried the shame of not being able to bear her own children, was hard on me. While many are missing, I have distinct memories of finding her sitting downstairs in the dark late at night. When I asked what was wrong, she would say that I was a “problem child,” and that she was going to “give me back.” I remember sitting on the floor at her knee, pleading with her not to give me away and promising I would be “good.” These experiences served to reinforce my imprint of abandonment.

bear her own children, was hard on me. While many are missing, I have distinct memories of finding her sitting downstairs in the dark late at night. When I asked what was wrong, she would say that I was a “problem child,” and that she was going to “give me back.” I remember sitting on the floor at her knee, pleading with her not to give me away and promising I would be “good.” These experiences served to reinforce my imprint of abandonment.

When angry, she would say, “Wait until your father gets home.” When he did, she would meet him at the door with a list of my wrongdoings. My father would then take off his belt and hit me across the back of the legs. Once, when I was in high school, I dropped off a friend on my way home. My mother, who had seen me come from the opposite direction of the school, met me at the door and accused me of skipping school and lying. The lesson I learned was that people hurt the people they love and the truth didn’t matter. I now understand why I engaged in substance abuse (drugs and alcohol) and self-harm (cutting). My mother died of cancer when I was seventeen. Sadly, the only written memory I have of her is a letter she wrote when I was a young teen highlighting everything they did for me and all the ways I disappointed them. I have kept it all these years.

In the Ten Principles of Mother-Infant Bonding: Foundations for Human Trust, Harmony & Peace, Prescott (n.d.) said that one of the ten principles of mother-infant bonding is that “emergent sexuality must be respected” (http://www.violence.de/prescott/ letters/10principles.pdf). Not so in my family of origin. Whenever my face broke out (acne), my mother accused me of having “sex thoughts” and told me how shameful that was. She said sex was “nasty, and that when your husband wanted it you prayed for it to be over soon, washed up quickly, and hoped he wouldn’t come near you again for a long time.” She also told me my birth mother was a “whore,” and that I was going to be just like her.

We want to believe what our mothers tell us is true. I remember being exceptionally curious about sex, and subsequently acted out my fair share of promiscuity at a very young age, having my first experience of sexual intercourse at fifteen. Research by Brown et al. (2015) showed “adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have been linked to early sexual debut” (Pg. 89). I now realize what I was really searching for was love and acceptance and to feel needed. When boys/men paid attention to me it felt good. Unfortunately, many of my experiences were not positive. For example, when I was eighteen, I joined the Army Reserves. The Major in my office repeatedly made sexual comments and threw peanuts down the front of my uniform and asked to “get them out”. During my out-processing, I was raped by one of the Captains.

Both flattered and ashamed, I didn’t tell anyone until years later. I blamed myself, thinking I had deserved this treatment. As Levine (1997) noted “compulsive, perverse, promiscuous…behaviors are common symptoms of trauma” (pg. 32).

In Chamberlain’s article The Sentient Prenate (1994), he reports that children who feel unwanted or abandoned “were more hyperactive,” “felt more rejected by their mothers,” “reported far more dissatisfaction, unhappiness, problems, and worries,” had “repeated disappointments with love relationships,” and “reported their marriages were less satisfying” (pg. 8).

In school, I was described as “very busy,” “very talkative,” and had “trouble sitting still.” I felt rejected by my adoptive mother and had experienced the ultimate rejection of being given away by my birth mother. Even today, I have a tendency towards dissatisfaction and unsettlement, dysthymia, and I worry excessively, especially around issues of safety, emotional security, and money. I now understand much of this was imprinted by my birth mother’s socio-emotional and financial state prior to and during her pregnancy with me, as well those early months spent in the orphanage. As for my own relationship/marital history, my love and sexual relationships have often felt unfulfilling and my first husband was emotionally and sexually abusive. His extensive travel schedule also triggered my imprints of abandonment and to self-sooth I engaged in extra-marital relationships. Even though my relationship with my second husband is entirely different, I still struggle with occasional feelings of insecurity and rejection (Emerson, 1995).

Mothering

Despite all of this I was committed to mothering differently than I had, and hadn’t, been mothered. There are, however four distinct memories that I still struggle with, times I slipped into my historical past. When my eldest was five, she ‘talked back’ and without even thinking I slapped her across the face. I remember we both experienced an intense sensation of shock—truly a traumatic moment that left its imprint on both our psyches.

Another time I called my middle daughter a “rotten little shit.” She laughed, but I felt shame. Once, when my eldest was acting out, I took her to the floor and said, “I brought you into this world, and I can take you out, so you better shape up.” I felt our mutual sense of helplessness.

Another time I called my middle daughter a “rotten little shit.” She laughed, but I felt shame. Once, when my eldest was acting out, I took her to the floor and said, “I brought you into this world, and I can take you out, so you better shape up.” I felt our mutual sense of helplessness.

Each of these experiences replicated aspects of my own upbringing. In their enactment, I was reliving the imprints. Seeking repair, I apologized. I still ‘own’ the final incident. During an argument with my eldest, I called her father (my first husband) upstairs for support. He came into the room, threw her to the floor, and started slapping her across the head and face. The younger two witnessed this. My (adult) children still blame me for calling out to him, and my heart aches with the memory.

One of the main reasons I left the marriage was because my daughter’s father parented in a way that I believed was harmful to our children. In essence, it was unconscious, emotionally distant, and abusive, much like his own mother had been.

Violence was normalized in my ex-husband’s family. He and his siblings were introduced to killing early on. For example, my ex was given the task of shooting ‘sick’ kittens. He bragged about putting mice in a jar filled with gasoline and setting fire to them when he was a teenager. One day I went to church with two of my daughters and came home to find my dog’s collar laying at the door.

When I asked where she was, he replied, “I shot her.” When I asked why he would do such a thing he said, “She was getting old and wasn’t useful anymore.” I asked him what he was going to do with me when he thought I was old and not useful anymore, and he said, “I’ll probably shoot you too.”

He believed the way you get children to behave was to make them afraid of what you will do to them if they didn’t. In contrast, I wanted my children to ‘trust their gut’. I believed that if I raised them mindfully, and sensitively, they would instinctually recognize right from wrong.

My ex also believed in physically overpowering or hurting someone to gain control (power). This was also a learned behavior. His father had beat his mother, and she hit her children. We know that the symptoms of this abuse show up much later in the form of behaviors (Copeland et al., 2018) (Copeland et al., 2018) and health issues. There has been more recent recognition that the impact may begin prenatally.

Of my ex’s seven other siblings: one (son) were abusive in his marriage; at least one daughter was the victim of domestic violence; one son died of brain cancer; one daughter died of colon cancer; one daughter has had breast cancer; one daughter attempted suicide and has since been diagnosed with cancer; and the youngest son committed suicide at nineteen. In my own family of origin, I am aware that all three of my sisters have been diagnosed with breast cancer and my mother died of complications of COPD. The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACES) clearly documents these illnesses, and others, as complications of childhood trauma.

Understanding the generational patterns of trauma, we can now see that there are many stories here— my birth mother’s, my adoptive mother’s, mine, my ex-husband’s mother’s, my ex-husband’s, and those of my three daughters. Had I not come to the study of prenatal and perinatal psychology, I might have never discovered any of this nor recognized that, as Peter Levine (2010) argues, “Trauma is not what happens to us, but what we hold inside in the absence of an empathetic witness” (pg. xii). Through APPPAH and the personal and professional work that subsequently ensued, I have finally become my own empathetic witness, and in turn I invite you to do the same. The Weinholds (2018) argue that “Given that up to eighty percent of those who have psychopathology and seek therapy have Disorganized Attachment (DA), there’s a high probability that a comparable percent of therapists also have DA” (pg. 242). They acknowledge that “Much of the harm that that does happen in clinical practice is unintentional, and happens through the mechanism of countertransference” (pg. 242). This is likely the result of the therapist not following the principle of “doing unto myself before doing to others” (pg. 242).

see that there are many stories here— my birth mother’s, my adoptive mother’s, mine, my ex-husband’s mother’s, my ex-husband’s, and those of my three daughters. Had I not come to the study of prenatal and perinatal psychology, I might have never discovered any of this nor recognized that, as Peter Levine (2010) argues, “Trauma is not what happens to us, but what we hold inside in the absence of an empathetic witness” (pg. xii). Through APPPAH and the personal and professional work that subsequently ensued, I have finally become my own empathetic witness, and in turn I invite you to do the same. The Weinholds (2018) argue that “Given that up to eighty percent of those who have psychopathology and seek therapy have Disorganized Attachment (DA), there’s a high probability that a comparable percent of therapists also have DA” (pg. 242). They acknowledge that “Much of the harm that that does happen in clinical practice is unintentional, and happens through the mechanism of countertransference” (pg. 242). This is likely the result of the therapist not following the principle of “doing unto myself before doing to others” (pg. 242).

In conclusion, it is vitally important for us as therapists and teachers to see trauma-informed awareness and care as both an opportunity and a gift to ourselves and our clients and students. Even though we may view ourselves as healthy and whole, when we are able to consciously and deliberately address our own prenatal and perinatal histories, as well as those of our clients and their ancestors, and when we are able to openly acknowledge both conscious and unconscious imprints, we are able to positively influence both the quantity and quality of learning and healing that takes place.

References

Brown, M., Masho, S., Perera, R. Mezuk, B., & Cohen, S. (2015). Sex: Results from a national representative sample. Child Abuse and Neglect. Vol. 46:89-102.

Chamberlain, D. (1994). The sentient prenate: What every parent should know. Journal of Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health, 28(4), 253-274.

Copeland, W., Shanahan, L., Hinesley, J, Chan, R., Aberg, K., Fairbank, J. & Costello, J. (2018). Association of childhood trauma exposure with adult psychiatric disorders and functional outcomes. JAMA Network Open 1(7).

Emerson, W. (1995). “The vulnerable prenate.” Paper presented to the APPPAH Congress, San Francisco. Levine, P. (1997). Waking the tiger: Healing trauma. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Levine, P. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. Prescott, J. W. (n.d.) Ten principles of mother-infant bonding: Foundations for human trust, harmony & peace. Institute of Humanistic Science.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Trauma-Informed Approach and Trauma-Specific Interventions. https://www.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions

Teyber, E. (2010). Interpersonal process in therapy: An integrative model (6th Ed.). Boston: Cengage Learning.

Trout, M. (n.d.). Searching for aunt Rosie: Accounting for non-clinical, benevolent influences on the lives of babies and young children. The Infant-Parent Institute. https://www.infant-parent.com/

Weinhold, B., & Weinhold, J. (2018). Developmental trauma: The game changer in the mental health profession (2nd Ed.). Colorado Springs: CICRCL Press.

Sally has worked in the birth field for over thirty years. She is a Certified Labor Assistant and has attended home births as an apprentice midwife and hospital births as a Doula. She received her Doctorate in Sociology and a Graduate Certificate in Feminist Theory from Binghamton University. Her dissertation was a tri-generational study of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors in pregnancy, birth, early mothering, and family healthcare. She taught for over 20 years at the university level, including ten years in Human Development and three years in Child and Family Studies. Her research areas are pregnancy and birth, prenatal and perinatal psychology, family health, and family violence. Sally is the Co-Director of Education for the Association for Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health (APPPAH) and is a faculty member with the Chicago- based HealthConnect One’s Birth Equity Leadership Academy (BELA). She also serves on the BirthWorks Board of Directors and is a Trainer for Birth Works Childbirth Education, Doula, and ACED (Advanced Childbirth Education Doula) workshops. She is the mother of three birth daughters, a son, and grandmother to nine.

Sally has worked in the birth field for over thirty years. She is a Certified Labor Assistant and has attended home births as an apprentice midwife and hospital births as a Doula. She received her Doctorate in Sociology and a Graduate Certificate in Feminist Theory from Binghamton University. Her dissertation was a tri-generational study of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors in pregnancy, birth, early mothering, and family healthcare. She taught for over 20 years at the university level, including ten years in Human Development and three years in Child and Family Studies. Her research areas are pregnancy and birth, prenatal and perinatal psychology, family health, and family violence. Sally is the Co-Director of Education for the Association for Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health (APPPAH) and is a faculty member with the Chicago- based HealthConnect One’s Birth Equity Leadership Academy (BELA). She also serves on the BirthWorks Board of Directors and is a Trainer for Birth Works Childbirth Education, Doula, and ACED (Advanced Childbirth Education Doula) workshops. She is the mother of three birth daughters, a son, and grandmother to nine.