Reviewed by Nancy Eichhorn

I finished reading The Shattered Oak: Overcoming Domestic Abuse and a Misdiagnosis of Mental Illness and realized I hadn’t drawn a full breath since page one. At some points in the text, I simply stopped breathing.

The character’s voice drew me in. It wasn’t necessarily the writing. At times there was just too much detail, so much so that it was repetitive. But Barbara’s first-person voice created an impact. She was distant in moments, disconnected from reality, and then smack dab in the brunt truth of her situation. She sounded emotionally and developmentally stunted; considering the content of her experiences, her tone of voice and language use rang true.

It’s amazing that her daughter wrote this, as if channeling her mother’s presence, letting her energy be on the page all the while having to relive not only her mother’s experiences but her own as she too dealt with the repercussions of her mother’s abusive situations.

I had difficulty fathoming the intensity of Barbara’s life, the chronic stress and abuse both self and other inflicted. And yet, I felt compelled to read her story, a sense of honoring her resilience, her courage, her attempts to maintain a positive position in dire situations. I appreciated her need to journal, to capture her thoughts and feelings on the page, a container for what she couldn’t comprehend herself at times.

The story starts in the middle of one-sided fist fight—an angry man pummeling his wife’s face again and again like a heavyweight boxer going after a title. He leaves her numb and broken on the kitchen floor. After he drives off, their three young daughters cautiously come downstairs to tend to their mother. They know the drill and fetch ice packs, spoon feed her with pureed baby food. She writes, “I am too weak to care, and my face too swollen. For the moment, everyone is scared and frightened of this demon in our house” (pg. 15).

The insanity of her story was mindboggling. She endured a torturous life from start to nearly finish. She had no rights, no freedom, she was “stripped naked to the core” (pg. 86) raised in abuse, married into abuse, and medically treated abusively (sent to a sanitarium, lock down ward after two hospital interventions for attempted suicide), even her trip to the National Institute of Health to participate in a clinical trial for Cushings Disease left her feeling like a “walking test tube”, a “human lab experiment” (pg. 99).

Her torment didn’t end with her eventual divorce. She craved peace yet when she grasped it, for just a moment, her past crowded in and sent her off the edge—literally. She jumped off a cliff into a river far below knowing she couldn’t swim, almost downing (her second suicide attempt, on a timeline, but she saved herself).

This sense of a continual cycle of abuse is familiar— people tend to be drawn, albeit unconsciously, into situations that fit their historical past as well as put blinders on and pray for the right outcome despite knowing it’s not going to come. But to be inflicted not only by laypersons (her parents, her husband) but also by medical clinicians? It was heart wrenching to hear her experience as she was forced to take mind numbing drugs, subjected to electric shock therapy to silence her into submission. She captured the essence of a human soul wasting away. Thank God an angel appeared in her life, a nurse who took time to notice, to care, to fight for Barbara’s rights.

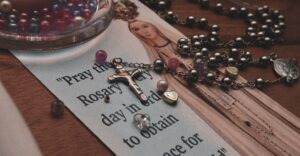

I couldn’t help but care about this woman. She was continually struck down, even her rosary beads were taken away. With steadfast faith, she visualized her beloved beads as she prayed again and again for God’s strength to survive the next worst thing. At one point, strapped to a medical table as if on a cross as electric shocks flowed throughout her body and out her feet, she compared her experience to that of Jesus on the cross. She dies inside but comes to life, finds the will to move forward with a positive approach to life. She sets her past behind to live in the present moment. At the end of story, she finds moments of release in nature.

The book ends with a postscript:

“On the very day we were doing our final edits before going to press, Barbara passed away. Her soul now is free . . .” (pg. 116).

Barbara’s story is not emotionally easy to read, and it has the potential to trigger readers’ emotional wounds from their own abusive pasts. And yet, it offers first person insight into experiences that clinicians might benefit understanding, that family members supporting loved ones recovering from abusive situations might gain some insight, and that survivors themselves might appreciate as they struggle with their own healing path.

Nancy Eichhorn, PhD is an accredited educator with a doctorate in clinical psychology, specializing in somatic psychology. Her current projects include publishing Somatic Psychotherapy Today, work as a writing mentor, workshop facilitator, freelance writer, and editor. Her writing resume includes over 5,000 newspaper and magazine articles, chapters in professional anthologies, including About Relational Body Psychotherapy and The Body in Relationship: Self-Other-Society. She is an avid hiker, kayaker, and overall outdoor enthusiast. Nature is her place of solace and inner expression.

Photo Credits:

Woman: Geralt Altmann from Pixabay

Rosary beads: Anuja Mary Tilj from Pixabay